The Smallest of Small:

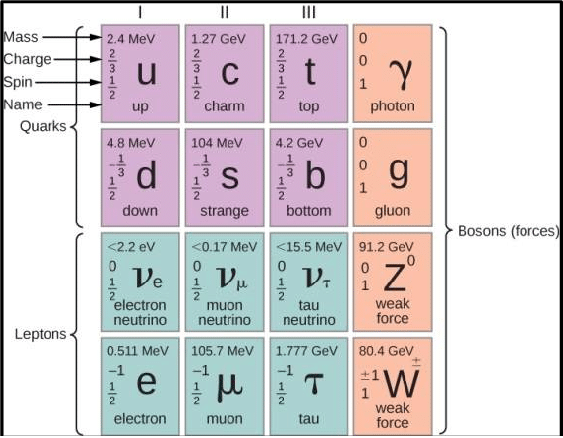

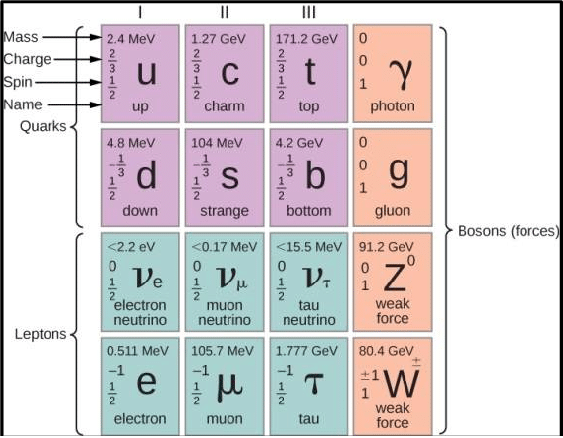

The Standard Model of Elementary Particles

Elementary or fundamental particles are subatomic particles that cannot be broken down further,

hence their being "fundamental." While subatomic particles were first identified in the 1930s,

the advent of quantum mechanics mechanics allowed scientists to break these particles down further, leading

to the development of the Standard Model of particle physics in the 1970s.

As the chart depicts, the Standard Model recognizes three categories of elementary particles: quarks,

leptons, and bosons. Each particle has certain qualities, including mass, charge, spin, and type or name.

Elementary particles are considered "point-like" particles, meaning they represent

a dimensionless "point" in space. Given they are microscopic and their masses are drastically

smaller than anything we interact with in our daily life, it is more appropriate, albiet less

intuitive, to conceptualize them as locations rather than objects. On the quantum level,

which deals with the microscopic realm, probability, speculation, and estimation play a large

role in determining where things are and how they behave.

Upon looking at the chart, something that may have caught your attention or confused you

is the description of boson particles as "forces." In physics, the four fundamental forces are

electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear forces, and gravity. By now,

you're likely aware of the elusive nature of elementary particles, but still, how can a dimensionless,

point-like particle be a force? It's important to clarify that the particles themselves are not

forces, but rather the carriers of three of the four forces: electromagnetism,

the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force.

But what about the fourth force? What about Gravity?

As it turns out, the only force that the Standard Model of elementary particles doesn't

account for is the gravitational force.

And since the Standard Model is a feature of quantum field theory, this points to an even bigger

problem: quantum mechanics and

gravity cannot coexist under this framework. And why does this

matter to physicists? Because a Theory of Everything would unify the four forces under a single

principle, meaning the Standard Model, as we understand it now, does not point to a Theory of

Everything.

Perhaps an amendment need be made to our beloved

point-like particle?